The androgynous heroine of the South Korean television hit Coffee Prince first appears on a rickety moped weaving through Seoul traffic. She's sometimes mistaken for a teenage boy, but she has bigger things on her mind, like making a living. She's an energetic eccentric with too many part-time jobs and too many bills to pay. And she's a beloved character for myself and the many Americans who watch subtitled Korean television in spite of the sexism present in many of these shows.

I have trouble explaining why I fell in love with Coffee Prince, a 2007 "gender bender" romantic comedy about a woman who disguises herself as a man to get a job—and then, somewhat predictably, falls in love. On paper, I hate this kind of story. Gender confusion is a good subject for a serious drama, but it quickly becomes trite when it's milked for comedy. The 2005 Twelfth Night adaptation She's the Man was the quintessential bad gender bender, relying on stereotypes too hackneyed to even be offensive. After seeing it on an airplane, I swore to avoid the entire genre.

In fact, on paper, I shouldn't like any Korean shows, aka K-dramas. They almost inevitably reflect South Korea's conservative gender politics. The female characters get bossed around. The male characters kiss women who don't want to be kissed. Everyone's parents want them to get married. One of the stock villains is the evil stepmother, but no one ever seems to have an evil stepfather.

But I'm not the only smart woman watching subtitled K-dramas. Nor am I the only feminist viewer. Audience numbers are hard to come by, but New York-based website DramaFever, an online video streaming service specializing in Asian television, tallies a monthly American viewership of 6 to 7 million. Americans also watch K-dramas on Netflix, Hulu, and other sites, so we can safely say the shows attract a sizable audience by today's standards. And 85% of American viewers are Anglophones without Asian heritage.

What's so compelling it can make up for behaviors that even male viewers recognize as misogynist?

I could argue that Korean shows run the gamut from good to bad, and claim that I only watch the good ones. But I'll admit I've sat through plenty of offensive scenes where the hero refers to his beloved as "his woman" and drags her around by the wrist like property. Another easy way out would be to say that I watch for pleasure, not politics. K-dramas are full of charismatic stars—real eye candy, a delight to watch. But ultimately, I can only spend time with fictional characters I connect with.

And here's the rub: Today's K-dramas resonate with me more than today's American shows because I can't relate to the people on American television.

Sympathetic, three-dimensional female characters have become scarce. The melodramas that provided good roles for actresses in the '90s (Ally McBeal, Daria, My So-Called Life, Buffy The Vampire Slayer . . . ) have gone out of style, to be replaced by zombies, superheroes, and various killers. The Good Wife is a rare exception. Most of our interesting female characters are confined to 22-minute sitcoms.

Coffee Prince demonstrates the power of a heroine we can relate to. The number one reason Coffee Prince charms us is simply because Eun-Chan, the lead character, is so charming—awkward without being self-conscious, optimistic without being a Pollyanna. The actress Yoon Eun-Hye brings to life her pride, temper, and insecurities, too, but still presents her as likable.

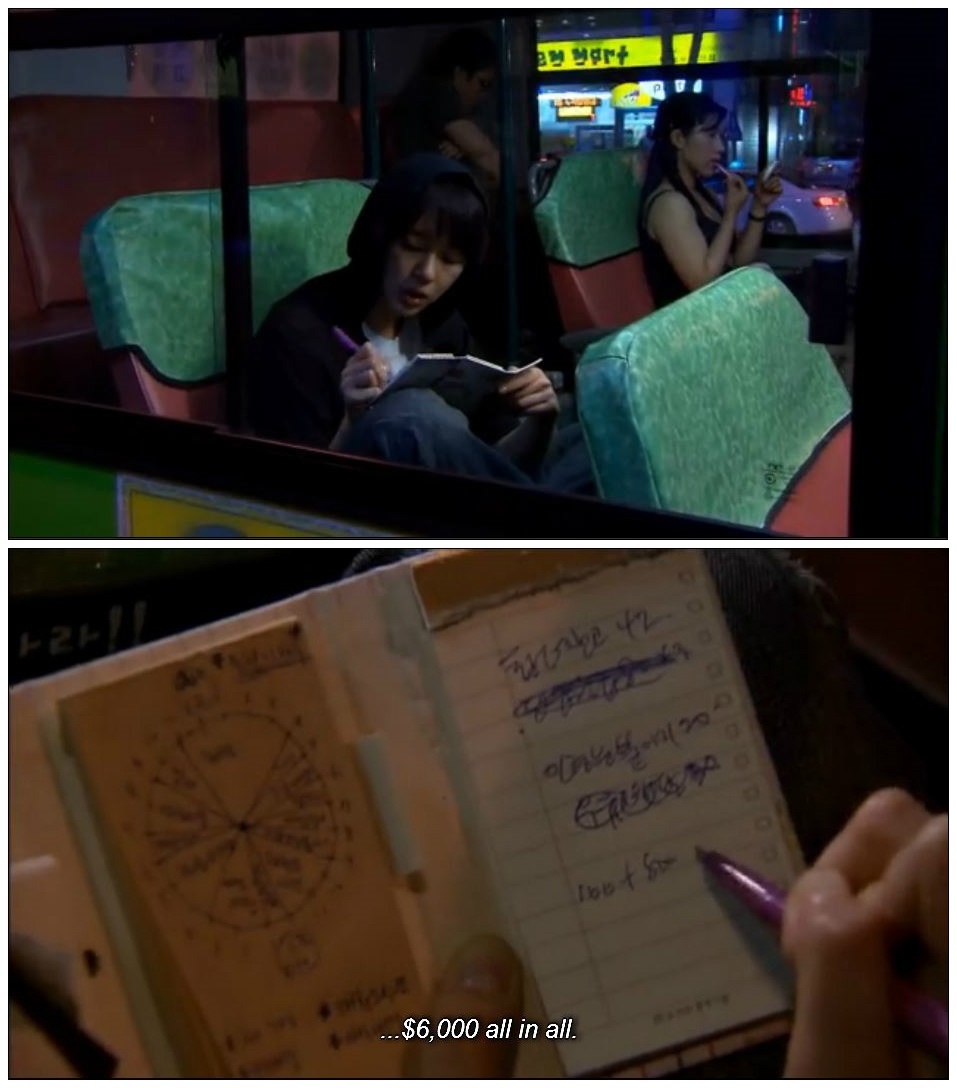

Eun-Chan is nothing like me in personality. And we speak different languages and follow different cultural expectations. But as she takes the public bus around town between part-time jobs, she's calculating and recalculating how to find enough cash to make rent—and seeing her do something I've done so many times, I feel like we're sisters. She's an everywoman because she worries about rent. She's an everywoman by being the socio-economic and psychological opposite of the wealthy neurotics in Girls.

Though Coffee Prince is on the surface a love story, it's also a story about money and class. It follows a reverse Cinderella formula popular in East Asian melodramas, in which the poor girl meets a rich prince and dislikes him because he acts entitled. Only once he learns Confucian values like hard work will she fall in love. This "Candy narrative" (so-called after the influential Japanese girls' comic) is a K-drama cliché, but to an American viewer it's a pleasant surprise to see the working class portrayed as proud rather than merely envious. The Candy formula places making a living at the center of a woman's story, as it often is in real life. Class conflict is a theme in many Korean romantic comedies, reflecting Korean social concerns that I can relate to. Though some K-dramas glamorize the rich, many skewer them.

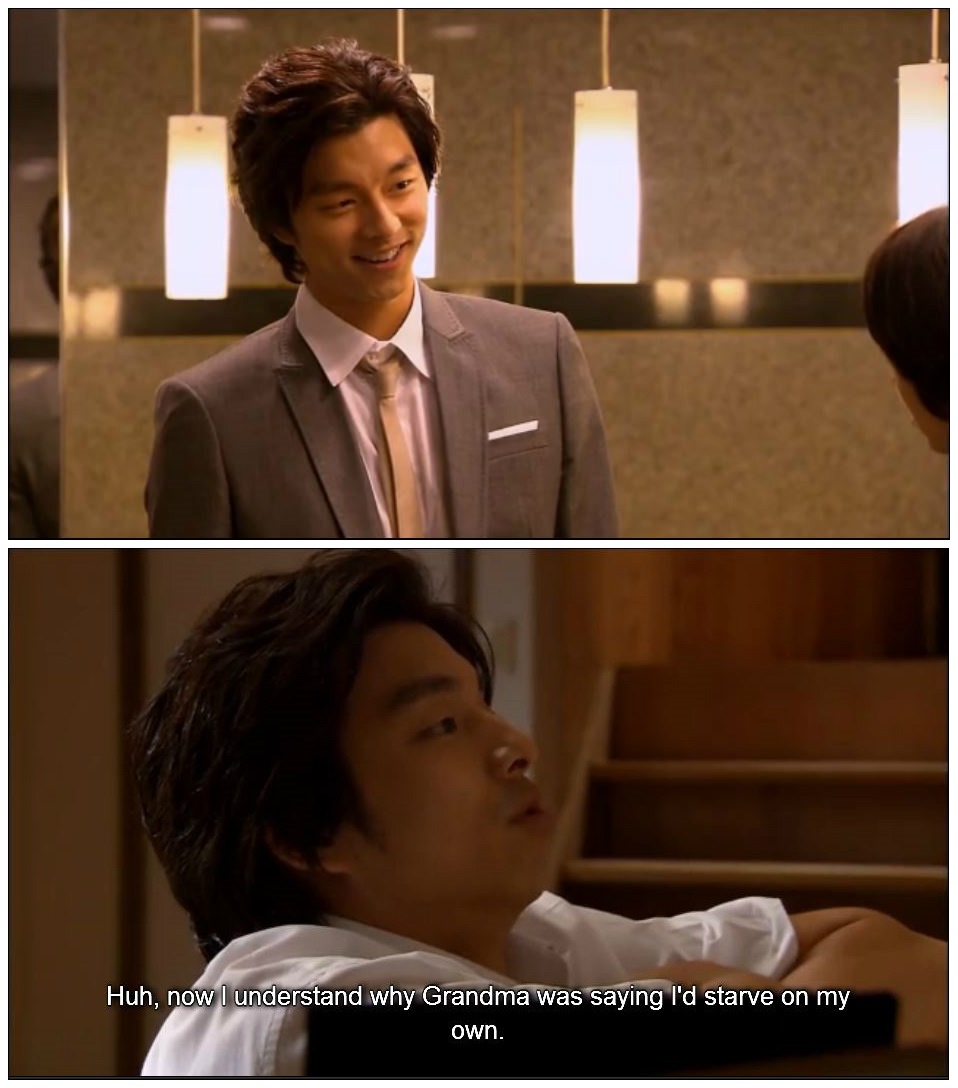

The second most-winning thing in Coffee Prince after the heroine is the hero, Choi Han-Gyul, played with pitch-perfect self-mockery by Gong Yoo. Like many male K-drama stars, he's a master at conveying the emotional vulnerability behind the arrogant façade. But the narrative also requires the character to shed his arrogance. In an era when American scriptwriters have succumbed to a bland Hobbesian pessimism about human nature, Korean television continues to tell stories in which flawed people make the effort to become less flawed.

The third reason to love Coffee Prince is simply that, like many K-dramas, it's a love story. American television used to tell love stories, but today we have to look to the newest season of Britain's Downton Abbey for in-depth, hour-long stories about relationships. And we've lost something with the decline in scripted shows about romance. A light entertainment like Coffee Prince forms part of a heavier cultural dialogue about how lovers should treat each other.

If we want to live in a society where men and women treat each other with equal dignity, we can't stop discussing how we define dignity. Men and women have to talk about what we want in an ideal world, instead of waiting for a Ray Rice partner-battering video to speak out about what we don't want. And we have to preserve an unfashionable optimism about human nature. In the real world, people do change for the better, which means societies can improve. What's the point of believing in equality if you don't believe we can change?

I can look past K-drama sexism for the simple reason that K-dramas are at least attempting to tell entertaining stories about likable women who work for a living and fall in love with decent men. It sounds like a straightforward formula. I wish American producers would try it out.

![By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Bell.png?itok=gWp6s_Y0)